Figure 1: Code of practice for consumer IoT security Source: Department for Digital Culture, Media and Sport

The IoT is proliferating, with around 66% of organisations currently using IoT and an install base of around 17 billion devices.

Analyst company Gartner believes spending is due to increase from an estimated $1.5bn in 2018 to over $3bn by 2020 with an estimated 30 billion devices, rising to 75 billion by 2025.

Until recently there had been few standards or regulations for cyber security of IoT devices and systems. Traditional information and cyber security approaches, such as ISO 27001 and the NIST Cyber Security Framework, were designed for enterprises, and while they are relevant they do not provide the focused guidance required for effective IoT security.

IoT cyber incidents

A further problem is that in the rush to develop and market IoT devices many of these products lacked effective security measures. Consequently, a large number of the solutions deployed are insecure and have open security vulnerabilities.

The Gartner 2018 survey found that nearly 20% of organisations had seen at least one IoT-based attack in the past three years. These included, in 2016, the Mirai botnet, which compromised vulnerable devices such as CCTV cameras and home routers and was used to perform a number of distributed denial of service attacks (DDoS), including one on some core internet services which resulted in services being unavailable to users in Europe and the US.

In another attack, customer data was stolen from a casino through an insecure internet-connected thermometer in a fish tank.

Over the past couple of years,the Brickerbot malware has been infecting IoT devices which have poor security and overwriting the firmware with random data, rendering the devices useless.

Multiple defences

In September 2018, California passed a law which states that any manufacturer of a device that connects directly or indirectly to the internet must equip it with “reasonable” security features, designed to prevent unauthorised access and modification. US federal legislators have at least five draft cyber‑security legislative proposals in process.

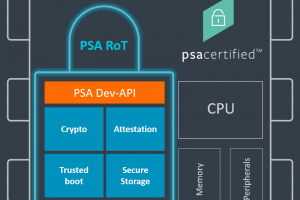

The EU has published best practice guidance and security requirements and in October the UK Department for Culture, Media and Sport published a Code of Practice for Consumer IoT Security. This promotes 13 guidelines for appropriate IoT security (Figure 1).

In the wider EU, ENISA (European Union Agency for Network and Information Security) has published Baseline Security Recommendations for IoT with a particular focus on critical national infrastructures. Industry initiatives have included the IoT Security Foundation’s Code of Practice, which provides a basis for testing and certification of IoT security.

While these are a great start, the problem is that, in the EU in particular, these practices are not mandatory. Regulators need to work out how effective standards and practices can be enforced pragmatically. The task for IoT device manufacturers is to ensure that products are “secure by design and by default”.

Historically, industry has been slow to adopt security standards, leading to the need for regulation. With such an active market, vendors can turn security from being an expense and a chore to a competitive advantage. Failure to adopt good practice voluntarily is likely to trigger an over‑reaction, with restrictive and stringent regulation being imposed. Although formal accreditation or certification for the IoT is some way off, suppliers should be self-certifying their products and services. There is no excuse for suppliers to provide devices and systems with unproven security.

IoT consumers also need to be more demanding about the security requirements they expect from products and be prepared to verify what they are being offered. This will give providers real incentives to include security by design and as default.

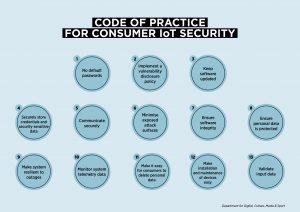

Even when individual products are security assured or certified the end‑to‑end solution will not necessarily be secure. Organisations integrating or using IoT solutions will still have to be satisfied that it is secured. This involves understanding the security and business risks, ensuring an end-to-end secure architecture and that testing has been carried out to meet all data privacy requirements (Figure 2).

The IoT offers clear business benefits but manufacturers, consumers and regulators all need to act now to provide the appropriate security.

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News